Here are a few suggestions for deepening your connection and communication when someone you love is dying:

Have eyes for the sacred. If possible, imagine that the territory you have entered is sacred ground, despite the terrible loss looming before you. Be open to the possibility that something transpersonal is occurring, and that the words you hear are tracking its course.

Validate your loved one’s words and experiences. Repeat back what your beloved has said, to let the person know you heard it: “Oh, your modality is broken. I would love to know more about that.” Avoid telling your beloved that what he or she is seeing or saying is wrong or “not real.”

Be a student of the language. Since you are in a new coun- try, learn its language. Study it. Practice it. Speak it. Listen for the symbols and metaphors that are meaningful to your beloved and then use them when you communicate. For example, ask, “Would you like me to help you find your passport?” When you hear things that sound nonsensical, simply think, “Oh, that’s how they phrase things in this country!”

Ask questions with authenticity and curiosity. It’s okay to let the dying person know you are confused and would love to hear more of what he or she wants to communicate. “Could you tell me more about...?”

Assume your loved one can hear you even when unresponsive or quiet; let the dying person know how deep your love goes. As we die, our sense of hearing is the last sense to go. When you are in another room, and especially when you are speaking about your beloved, speak with lots of praise and gratitude. Speak words that will bring joy or comfort to the person.

Savor silence. Sometimes it is better to just sit with your loved one. When words don’t build bridges, know that the dying may be much more attuned to telepathic or other nonverbal com- munication, much like the kind of communication we experience when we pray. Speak to the person you love as you would in prayer.

Imagine that the language that you hear is much like the language of another country that you do not know but has its own sets of meanings and functions. You would not judge the language of another country as being less valid than the language you speak. You might be curious and want to learn more, taking note of new words, new ways of saying things, or even new ways of seeing things.

This is the mindset of the FWP. Until we know differently, FWP assumes that the language at end of life has some kind of organization to it--that there are patterns in symbols, themes, grammar--even, if not especially, in the language that does not seem to make sense.

Healing Our Grief

A Final Words Journal

Keep a journal of the words you hear. Remember that the words that don't make sense are as important as the ones that do. Notice metaphors or symbols that are repeated. Also notice words that seem to contradict themselves. Are there certain colors that emerge? Are there references to people or places you do not see?

What might seem senseless to a stranger, may hold deep personal meaning to you. Sometimes meanings may not be clear at first, but when you begin to write about the words you have heard, you may find comforting or healing associations.

Jewels often emerge as we listen closely and write down final words, and the transcription process can help us feel more connected to our loved ones. Many times the dying say things that don’t make sense at the moment, but months or years later, you will find hints of prophecy or answers to questions in those words.

Free Associate Meanings from the Final Words

Final words can be like dreams. We learn so much by reflecting upon them and freely associating connections. Freely associate upon the meanings to the words you transcribe. Imagine the words are like an oracle, or the wisdom of dreams, let them invoke images and reflections within you. You may be surprised and also moved by what emerges. Remember, your associations, like the words themselves do not need to make sense. Connections often become clearer in time.

Have eyes for the sacred. If possible, imagine that the territory you have entered is sacred ground, despite the terrible loss looming before you. Be open to the possibility that something transpersonal is occurring, and that the words you hear are tracking its course.

Validate your loved one’s words and experiences. Repeat back what your beloved has said, to let the person know you heard it: “Oh, your modality is broken. I would love to know more about that.” Avoid telling your beloved that what he or she is seeing or saying is wrong or “not real.”

Be a student of the language. Since you are in a new coun- try, learn its language. Study it. Practice it. Speak it. Listen for the symbols and metaphors that are meaningful to your beloved and then use them when you communicate. For example, ask, “Would you like me to help you find your passport?” When you hear things that sound nonsensical, simply think, “Oh, that’s how they phrase things in this country!”

Ask questions with authenticity and curiosity. It’s okay to let the dying person know you are confused and would love to hear more of what he or she wants to communicate. “Could you tell me more about...?”

Assume your loved one can hear you even when unresponsive or quiet; let the dying person know how deep your love goes. As we die, our sense of hearing is the last sense to go. When you are in another room, and especially when you are speaking about your beloved, speak with lots of praise and gratitude. Speak words that will bring joy or comfort to the person.

Savor silence. Sometimes it is better to just sit with your loved one. When words don’t build bridges, know that the dying may be much more attuned to telepathic or other nonverbal com- munication, much like the kind of communication we experience when we pray. Speak to the person you love as you would in prayer.

Imagine that the language that you hear is much like the language of another country that you do not know but has its own sets of meanings and functions. You would not judge the language of another country as being less valid than the language you speak. You might be curious and want to learn more, taking note of new words, new ways of saying things, or even new ways of seeing things.

This is the mindset of the FWP. Until we know differently, FWP assumes that the language at end of life has some kind of organization to it--that there are patterns in symbols, themes, grammar--even, if not especially, in the language that does not seem to make sense.

Healing Our Grief

A Final Words Journal

Keep a journal of the words you hear. Remember that the words that don't make sense are as important as the ones that do. Notice metaphors or symbols that are repeated. Also notice words that seem to contradict themselves. Are there certain colors that emerge? Are there references to people or places you do not see?

What might seem senseless to a stranger, may hold deep personal meaning to you. Sometimes meanings may not be clear at first, but when you begin to write about the words you have heard, you may find comforting or healing associations.

Jewels often emerge as we listen closely and write down final words, and the transcription process can help us feel more connected to our loved ones. Many times the dying say things that don’t make sense at the moment, but months or years later, you will find hints of prophecy or answers to questions in those words.

Free Associate Meanings from the Final Words

Final words can be like dreams. We learn so much by reflecting upon them and freely associating connections. Freely associate upon the meanings to the words you transcribe. Imagine the words are like an oracle, or the wisdom of dreams, let them invoke images and reflections within you. You may be surprised and also moved by what emerges. Remember, your associations, like the words themselves do not need to make sense. Connections often become clearer in time.

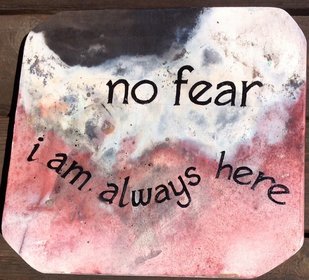

Create Art

I created raku-fired plaques of my father's final words as a way to honor his memory. Art is a powerful healing tool. Sometimes we need to move away from the words themselves and allow other modalities to move through as we heal.

I created raku-fired plaques of my father's final words as a way to honor his memory. Art is a powerful healing tool. Sometimes we need to move away from the words themselves and allow other modalities to move through as we heal.